Nutty Putty Cave was once one of Utah’s most beloved and frequently visited natural attractions. Discovered in 1960, the cave drew thousands of visitors every year—Boy Scout troops, college students, and curious adventurers eager to test themselves against its narrow, twisting passages. But its reputation changed forever in 2009, when a tragic accident claimed the life of 26-year-old medical student John Edward Jones. What was meant to be a family adventure turned Nutty Putty Cave into a permanent tomb and a grim reminder of the dangers hidden beneath the earth.

A Wrong Turn Into Disaster

On November 24, 2009, John Jones returned to Utah with his family for the Thanksgiving holiday. He, his younger brother, and several friends decided to explore Nutty Putty Cave—a nostalgic activity from their youth. Although John had some caving experience, it had been years since he had last crawled underground.

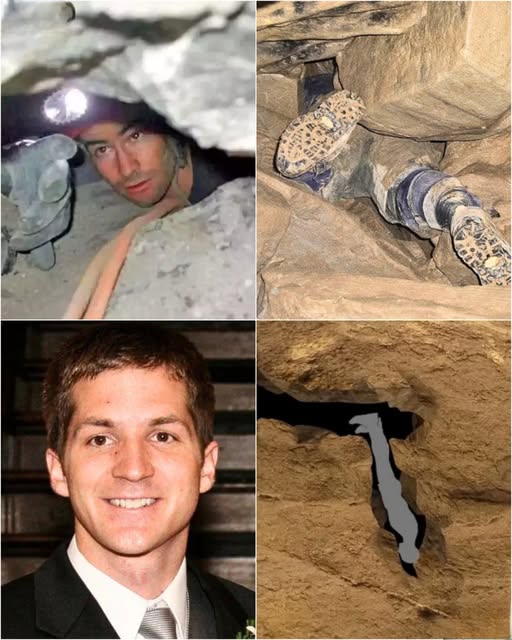

Late that evening, the group set out to locate one of the cave’s most famous tight passages: the “Birth Canal.” Believing he had found the correct tunnel, John crawled headfirst into a narrow, waist-high opening. But instead of widening, the passage narrowed further. In an attempt to back out, John likely inhaled, shrinking his chest just enough to slip deeper—straight into a downward, almost vertical fissure.

In seconds, he was trapped.

Pinned upside down at nearly a 70-degree angle, his arms stuck to his sides, he was unable to move forward or backward. His younger brother tried to pull him free, but it was impossible. Even at that moment, the family knew the situation was serious. They called for help immediately.

The 27-Hour Rescue Attempt

Rescue teams arrived quickly, launching what would become one of the most complex and exhausting cave rescue missions in Utah’s history. More than 137 volunteers, cavers, paramedics, and technical specialists gathered through the night to save John.

One of the first rescuers to reach him was Susie Motola, a small-framed, experienced caver who could navigate passages too narrow for most people. She spent nearly two hours trying to reposition John, make space around him, or simply keep him calm. Despite her efforts, nothing worked. The limestone around him was fragile, and every attempt to make room risked causing a collapse.

When manual efforts failed, rescuers constructed an elaborate pulley system, drilling anchors directly into the cave walls. It took hours to install the equipment in the cramped, suffocating space. By then, John had been upside down for nearly 19 hours—a dangerous position that caused blood to pool in his head and chest, placing enormous stress on his heart.

When rescuers finally began lifting him, disaster struck. The rope system snapped from the combined force of John’s weight and the rescuers’ pull. One rescuer was knocked unconscious by a flying carabiner. Once the system failed, there was no safe way to reinstall it.

John’s strength waned. His responses grew faint, then stopped. Eventually, he slipped into unconsciousness. When the last rescuer reached him to check his vital signs, he found no clear heartbeat or breathing. A paramedic confirmed the worst: John had died deep within the cave, just moments before midnight.

A Cave Beautiful, Complex, and Dangerous

Nutty Putty Cave was extraordinary in its geological structure. Unlike most caves formed by water seeping downward, Nutty Putty was a hypogenic cave, carved from below by hot, mineral-rich water forced upward through limestone. This created a labyrinth of tight squeezes, sudden drops, domed chambers, and twisting three-dimensional passages.

The cave was lined with a unique, claylike material nicknamed “nutty putty” for its strange consistency—solid until touched, then soft and elastic like Silly Putty. Adventurous but unpredictable, the cave had long been known for its tricky passages: The Helmet Eater, The Scout Eater, and of course, the Birth Canal. From 1999 to 2004, six people had already required rescue after getting stuck. All survived, but authorities grew increasingly concerned.

The cave closed in 2006 for safety reasons and reopened only months before John’s accident.

A Final Resting Place and a Lasting Warning

John’s death shook the Utah caving community. Many rescuers suffered trauma from the experience; some never entered a cave again. When experts concluded that removing John’s body was impossible without risking more lives, officials and family members made an agonizing decision: Nutty Putty Cave would be permanently sealed.

Today, the entrance is covered in concrete and marked with a memorial plaque for John Edward Jones. The cave, once full of laughter and adventure, now stands as a grave—frozen in time.

John’s story, like those of Floyd Collins in Kentucky or the Mossdale Caverns tragedy in England, is a reminder that the underground world demands respect. Caving can be thrilling and beautiful, but without preparation, training, and caution, even the most seemingly harmless passage can become deadly.

Nutty Putty Cave will never reopen. But its legacy endures, urging future explorers to approach the unknown with humility and care.