1776 — Local merchants in Glasgow, Scotland, who profited from the selling of American tobacco in Holland and France, were encouraged to “stimulate [their] correspondents and agents [in Virginia and Maryland]. . .to side with the King. . .”

———-

1776 — General John “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne’s play “The Blockade of Boston” was interrupted when colonists attack Charlestown. Unbeknownst to most, General John Burgoyne, the famous British General who surrendered his army at Saratoga, changing the course of the American Revolution, was also a mildly successful playwright.

Burgoyne published his first play, “The Maid of the Oaks,” in 1774. It was well received and soon opened at the Drury Lane Theater for a run of several nights to both good and bad reviews, but Burgoyne had established his name as a playwright. When Burgoyne was sent to Boston in May 1775, he used his influence to have Faneuil Hall converted into a theater. One of the ways bored British soldiers trapped in Boston spent their time was in producing plays twice a week on the upper level of Faneuil Hall, to the complete consternation of Boston’s Puritan population, which had outlawed theater performances since 1750, believing them to be instigators of “immorality, impiety, and contempt of religion.

While in Boston, Burgoyne wrote “The Blockade of Boston,” a satirical play making fun of the colonists. No complete copy of the play has survived, but one diary account says George Washington was portrayed as an “uncouth countryman; dressed shabbily, with a large wig and long rusty sword.” One line from an American character in the play reveals how the Americans were portrayed: “Ye tarbarrell’d Lawgivers, yankified Prigs, Who are Tyrants in Custom, yet call yourselves Whigs; In return for the Favours you’ve lavish’d on me, May I see you all hang’d upon Liberty Tree.”

The “Blockade of Boston” was set to be performed at 9pm on January 8, 1776. Burgoyne was not even in town anymore, having left for London in December. Just as the play was about to begin, a group of 100 colonists under the command of Major Thomas Knowlton staged a raid on the British outpost in Charlestown, across the water from Boston. Several homes were burned and five soldiers were captured in the raid.

As shots rang out from the Fort on Bunker Hill, the soldiers back in Boston heard the commotion. One soldier, dressed in a costume and about to perform, rushed onto the stage and yelled out that the rebels were attacking. The audience of mostly soldiers believed the outburst was part of the performance and stayed in their seats. After some more pleading by the officer/actor, the crowd realized they were truly under attack and began to scramble to their posts.

Eyewitness accounts have the soldiers tripping over each other, jumping over the orchestra pit, stomping on violins, rushing to change from their costumes, and wiping the makeup off their faces in order to get to their posts. The Americans had quite a laugh at the scene when it was reported in newspapers a few days later.

John Burgoyne would go on to publish three more successful plays in London but would never become a well-known playwright. He is most remembered for his surrender at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777, the event that encouraged France to join the war on the side of the Americans.

———-

1777 — The British withdrew all forces from New Jersey except posts at W. Brunswick and Perth Amboy.

1777 — WILLIAMSBURG. WANTED immediately, three or four SHOP JOINERS, also ten or twelve NEGRO CARPENTERS for six or seven months, for which a good price will be given by FRANCIS JARAM. N.B. Any person who has WHITE OAK TREES to dispose of, near this city, may apply as above. — Virginia Gazette [A joiner is a craftsman who does lighter and more ornamental work than a carpenter.]

1779 — Actions at Fort Morris (Sunbury), Georgia continued (January 6-9). General Augustine Prevost assumed command of British forces in the South and proceeded to initiate offensive operations. A skirmish commenced on January 6, when a force of 2,000 British engaged a much smaller force of 200 Continentals led by Major Joseph Lane. After Prevost positioned his artillery Lane surrendered. Each side incurred only minor casualties.

1781 — The mutiny of the Pennsylvania Line continued (January 1-10). Winter inactivity combined with grievances concerning enlistment terms, pay, and food, among other things, culminated in mutiny in the Continental camp located near Princeton, New Jersey. Little is known about how the mutiny was organized. The two leaders were William Bozar and John Williams. Only two individuals are recorded as having died in the mutiny. The mutineers intended to confront the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. General “Mad” Anthony Wayne managed to defuse the situation on which the British hope to capitalized. However, almost half the soldiers involved in the mutiny left the army.

———-

1790 — Heeding the Constitution’s directive that the President “shall from time to time give to the Congress Information on the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient,” George Washington addressed the House and Senate in New York City. He spoke of such pertinent matters as “the recent accession of the important state of North Carolina,” “certain hostile tribes of Indians,” and the need for “uniformity in the currency, weights, and measures of the United States.” The speech isn’t completely dated, however: he also emphasized “the promotion of science and literature” in the republic — a message as relevant today as it was then. His was the first stand-alone State of the Union address, though it was then called the “Annual Message.” (Washington had combined the previous year’s Annual Message with his Inaugural Address in April 1789.) It was also the shortest speech of its kind, at 1,089 words.

Washington began by congratulating you on the present favourable prospects of our public affairs, most notable of which was North Carolina’s recent decision to join the federal republic. North Carolina had rejected the Constitution in July 1788 because it lacked a bill of rights. Under the terms of the Constitution, the new government acceded to power after only 11 of the 13 states accepted the document. By the time North Carolina ratified in November 1789, the first Congress had met, written the Bill of Rights, and dispatched them for review by the states. When Washington spoke in January, it seemed likely the people of the United States would stand behind Washington’s government and enjoy the concord, peace, and plenty he saw as symbols of the nation’s good fortune.

Washington’s address gave a brief, but excellent, outline of his administration’s policies as designed by Alexander Hamilton. The former commander in chief of the Continental Army argued in favor of securing the common defence [sic], as he believed preparedness for war to be one of the most effectual means of preserving peace. Washington’s guarded language allowed him to hint at his support for the controversial idea of creating a standing army without making an overt request.

The most basic functions of day-to-day governing had yet to be organized, and Washington charged Congress with creating a competent fund designated for defraying the expenses incident to the conduct of our foreign affairs, a uniform rule of naturalization, and Uniformity in the Currency, Weights and Measures of the United States.

After covering the clearly federal issues of national defense and foreign affairs, Washington urged federal influence over domestic issues as well. The strongly Hamilton-influenced administration desired money for and some measure of control over Agriculture, Commerce, and Manufactures as well as Science and Literature. These national goals required a Federal Post-Office and Post-Roads and a means of public education, which the president justified to secure the Constitution, by educating future public servants in the republican principles of representative government.

———-

1811 — In Louisiana, a 500-slave revolt was led by Charles Deslondes at the German Coast. The revolt lasted two days

1811 — Missouri petitioned for statehood.

———-

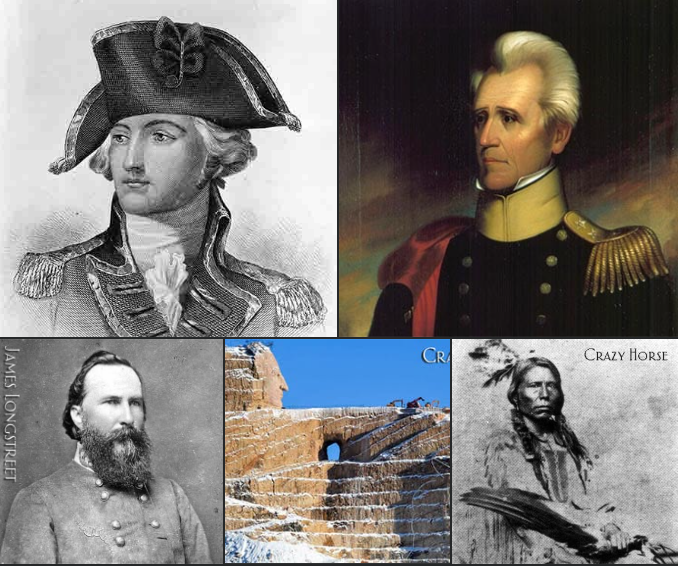

1815 — Major General Andrew Jackson led a small, poorly-equipped army to victory against eight thousand British troops at the Battle of New Orleans. The victory made Jackson a national hero. Although the American victory was a big morale boost for the young nation, its military significance was minimal as it occurred after the signing (although before ratification) of the Treaty of Ghent that officially ended the war between the U.S. and Great Britain. The battle was fought before word of the Treaty reached the respective armies in the field. The anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans was widely celebrated with parties and dances during the nineteenth century, especially in the South. General Andrew Jackson and his troops won the decisive Battle of New Orleans in the waning moments of the War of 1812.

Although the war had officially ended two weeks earlier with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, news of the treaty had not yet reached the United States from Europe, and military clashes between the British and the Americans continued. After a three-year struggle against superior British land and naval forces, the outnumbered American Army and Marines succeeded in preventing the British from gaining a foothold in the southern territories of Louisiana and western Florida.

The Battle of New Orleans engendered a sense of nationalism among Americans–after all, the fledgling nation had now beaten back the British empire twice in 30 years, first during the American Revolution and then in the War of 1812. Pride over the victory effectively ended the growing pains of political divisiveness that had plagued the United States at the beginning of the war. Winning the Battle of New Orleans not only helped the United States maintain its newly won independence and increased patriotic sentiment, it turned Jackson into a national hero and paved the way for his ascent to the presidency in 1828.

Jackson, independent, resourceful and tough, epitomized the national image of the American frontiersman. Early in the War of 1812, he earned the grudging respect of his soldiers, and the nickname Old Hickory, when he refused an order to disband his troops in Mississippi and instead marched them back to their base in Tennessee. His bold leadership, humble background, and relentlessness inspired the ragtag American Army at New Orleans. His image as a citizen-soldier and common man contributed to Jackson’s nationwide popularity.

———-

1818 — Yearly increase in manufacturing dropped nearly 80% in 1817 over 1816.

———-

1821 — Confederate General James Longstreet was born near Edgefield, South Carolina. Longstreet became one of the most successful generals in the Confederate army, but after the war he became a target of some of his comrades, who were searching for a scapegoat.

Longstreet grew up in Georgia and attended West Point, graduating in 1842. He was a close friend of Ulysses S. Grant and served as best man in Grant’s 1848 wedding to Julia Dent, Longstreet’s fourth cousin. Longstreet fought in the Mexican War (1846-48) and was wounded at the Battle of Chapultepec. He resigned from the U.S. military at the beginning of the Civil War, when he was named brigadier general in the Confederate army.

Longstreet fought at the First Battle of Bull Run, Virginia, in July 1861, and within a year was commander of corps in the Army of Northern Virginia under General Robert E. Lee. Upon the death of General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, in May 1863, Longstreet was considered the most effective corps commander in Lee’s army. He served with Lee for the rest of the war–except for the fall of 1863, when he took his force to aid the Confederate effort in Tennessee.

Longstreet was severely wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness in Virginia in May 1864 and did not return to service for six months. He went on to fight with Lee until the surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, in April 1865. After the war, Longstreet was involved in a number of businesses and held several governmental posts, most notably U.S. minister to Turkey. Although successful, he made two moves that greatly tarnished his reputation among his fellow Southerners: He joined the despised Republican Party and publicly questioned Lee’s strategy at the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. His fellow officers considered these sins to be unforgivable, and former comrades such as generals Jubal Early and John Gordon attacked Longstreet as a traitor. They asserted that Longstreet was responsible for the errors that lost Gettysburg.

Longstreet outlived most of his comrades and detractors before dying at age 82 on January 2, 1904. His second wife, Helen Dortch, lived until 1962.

———-

1835 — The United States national debt was zero for the only time. Andrew Jackson is shaking his skeletal head, pissed that a bunch of profligate Americans have soiled his legacy.

As president, Jackson was responsible for the first and only time the country stood at a true Debt Zero. The debt was $58.4 million when he first took office in 1829; six years later, as he would announce in his 1835 State of the Union, the country was finally in the black, with $440,000 in the bank. All it took to get there was a maniacal devotion to small government, the forced removal of tens of thousands of Native Americans, and tariffs so high the union nearly broke apart. The kind of thing that’s easily replicable in 2011.

So, while we’re counting down the days until the U.S. bursts through the ceiling like a Roald Dahl character, let’s dwell on a different timeline: Andrew Jackson’s. It’ll remind you that Debt Zero doesn’t happen overnight.

1795: For Jackson, debt became his white whale from an early age. Before he went to battle and burnished his Old Hickory* legacy, he was a lawyer and real-estate man, and a rich one at that. When Jackson was 32, he sold 68,000 acres of land to a guy named David Allison. But Allison didn’t have the most stable of financial lives, and soon ended up declaring bankruptcy and rotting in a debtor’s prison, where he’d die in 1798. Jackson, meanwhile, was left in a lurch, having used the promise of Allison’s money to start buying supplies for a trading post he was starting. According to John Steele Gordon’s surprisingly readable history of U.S. debt, Hamilton’s Blessing, Jackson would spend the next 15 years sorting it all out.

1824: When Jackson first unsuccessfully campaigned for president he did it on a platform that would make Tea Partiers blush. He framed the federal debt as an almost-spiritual affliction, calling it “a national curse.” As Jon Meacham writes in, American Lion, his Pulitzer-winning biography of Jackson: “To him, debt was dangerous, for debt put power in the hands of creditors—and if power was in the hands of creditors, it could not be in the hands of the people, where Jackson believed it belonged.”

1828: Likewise, he was adamant power not be in the hands of the Brits. The country’s protectionist streak meant a series of tariffs were passed to help build the economy. Starting in 1824, when Jackson was still a Senator, he voted in favor of tariffs to raise revenue on imports and help the country’s fledgling manufacturing industry compete with Britain’s. 1828′s Tariff Act, menacingly nicknamed the “Tariff of Abominations,” was especially restrictive, and South Carolina, whose economy was already suffering, was furious (again—some things never change) that the legislation would raise duties from 33 to 50 percent, reinforce Britain’s unwillingness to import its cotton and keep prices on manufactured goods from the north high. The Union was threatening to fracture, but the Treasury was getting rich. Tradeoffs.

1829: Once he took office, Jackson finally had enough power to spear the debt, pursuing it single-mindedly, no matter the costs. He refused to finance state projects with federal funds, partly because he believed in a small federal government, and partly because it would cost too much. Predictably, congressmen who were trying to get funding for local projects (proto-pork!) were angry, but Jackson wouldn’t budge. In 1830, he threatened to veto any funding for state infrastructure. “I stand committed before the country to pay off the national debt at the earliest practicable moment,” he told a Kentucky congressman seeking funding. “Are you willing–are my friends willing to lay taxes to pay for internal improvements?–for be assured I will not borrow a cent except in cases of absolute necessity!” The Congressman replied, “No, that would be worse than a veto.”

1830: Congress passes the Indian Removal Act of 1830, offering 25 million acres of new land in exchange for the forced eviction of tens of thousands of Native Americans. That land was later sold, and between 1832 and 1836 federal land sales increased 1,000 percent, bringing more than $25 million into federal coffers in 1836 alone. The U.S. was committing human-rights atrocities, but the Treasury was getting rich. More tradeoffs.

1832: Jackson was now President, and South Carolina’s anger finally boiled over. It threatened to circumvent federal law and lift the tariffs on British imports, both lowering plantation owners’ costs and reopening a market. Jackson, with the end of the federal debt in sight, agreed to relax the tariffs and coaxed South Carolina off the ledge. Twenty-nine years later, they would push back over by taking the first shots of the Civil War.

1835: It only took 40 years, but Jackson had finally done it—exorcised both him and the country of its debt curse. “Free from public debt, at peace with all the world,” he wrote to Congress. The U.S. was finally debt-free. The Democrats held a banquet to celebrate, but Jackson was too modest to attend. No reason to celebrate what was sure to be the new normal.

2019: The US hasn’t reached Debt Zero since.

———-

1838 — Alfred Vail demonstrated a telegraph system using dots and dashes—the forerunner of Morse code.

1861 — Jacob Thompson of Mississippi, Secretary of Interior and the last Southerner in Lincoln’s Cabinet, resigned.

1862 — Frank Nelson Doubleday, American publisher, was born (d. 1934).

1862 — Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson is famous for being both a brilliant fighting general, as well as something of an eccentric, perpetually sucking on lemons. As it turns out many of these stories are just that, or at best exaggerations. Jackson held many beliefs that, while common today, were indeed odd in his own time. His health, particularly eyesight and digestion, was poor for most of his life and he ate fruits and vegetables whenever possible to help this. He also believed in the importance of bathing, to such an extent that today, with his forces horribly weary after marching and fighting in severe cold, he called a halt for rest at Unger’s Store, Virginia, and Jackson ordered water heated. On this day, both he and his men indulged in baths.

1863 — Gen. John Sappington Marmaduke, CSA, was on an expedition through Missouri this winter, in another attempt to carve the border state out of Union control and into the Confederacy. The campaign out of Arkansas had gone reasonably well up until two days ago when the town of Ozark had been successfully taken. The march then led to Springfield, Missouri, but a difference arose: Springfield was defended by a Union garrison. A battle naturally was conducted, and Marmaduke’s men suffered a setback. The garrison defended Springfield successfully, and Marmaduke withdrew a short distance. The garrison did not, however, pursue.

1864 — While there were many changes and innovations in warfare during the War for Southern Independence, one item remained as it has always been: there was no mercy given to captured spies. A Confederate agent named David O. Dodd, paid the ultimate price for his activities on this day, after a trial which caused a considerable uproar in the Western area, although it was little covered in the Eastern press. Captured in Little Rock and tried there, he was today hanged there. All over the western area changes were happening rapidly. A meeting was held in New Orleans of Union sympathizers, to organize reconstruction efforts.

1865 — With Gen. Ben Butler now replaced by the vastly more capable Gen. Alfred H. Terry in command of the Army side of the project, the effort to capture Ft. Fisher was in full stride today. An immense fleet had been assembled by Admiral David D. Porter, half gunships and the other half troop transports for the Army force. To allow for the fact that bad weather could blow in unexpectedly at any time, the fleet had scheduled a rendezvous point in case regrouping was needed. They arrived at this point, off Beaufort, North Carolina, today, and indeed had to wait for a few vessels to catch up, although the reasons were more mechanical than meteorological. The weather was holding, which did not bode well for the defenses of Wilmington, North Carolina.

———-

1837 — Kentucky rejected the 14th Amendment.

———-

1867 — Congress overrode President Andrew Johnson’s veto of a bill granting all adult male citizens of the District of Columbia the right to vote, and the bill became law. It was the first law in American history that granted African-American men the right to vote. According to the terms of the legislation, every male citizen of the city 21 years of age or older has the right to vote, except welfare or charity recipients, those under guardianship, men convicted of major crimes, or men who voluntarily sheltered Confederate troops or spies during the Civil War. The bill, vetoed by President Johnson on January 5, was overridden by a vote of 29 to 10 in the Senate and by a vote of 112 to 38 in the House of Representatives.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the Republican-dominated Congress sought to enfranchise African-American men, who thus would be empowered to protect themselves against exploitation and strengthen the Republican control over the South. In 1870, in a major victory in this crusade, the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, prohibiting all states from discriminating against potential male voters because of race or previous condition of servitude.

———-

1867 — Emily Balch was born in Jamaica Plain. Her parents’ affluence and enlightened views allowed her to attend college at a time when few women did. She entered Bryn Mawr in 1886 and graduated with honors three years later. After studying abroad and helping start a settlement house in Boston, she decided on an academic career. She taught at Wellesley for 22 years until her growing political activism and her opposition to U.S. entry into World War I cost her her job. For the rest of her long life, she devoted her talent and energy to organizing women on behalf of world peace. In 1946 her accomplishments were recognized when she was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace.

1877 — Francis Nicholls, a Confederate general was inaugurated as Louisiana’s governor. Stephen B. Packard, a Republican, tried to claim victory.

———-

1877 — Oglala Lakota Crazy Horse and his warriors—outnumbered, low on ammunition, and forced to use outdated weapons to defend themselves—fought their final losing battle against the U.S. Cavalry in Montana.

Six months earlier, in the Battle of Little Bighorn, Crazy Horse and his ally, Chief Sitting Bull, led their combined forces of Sioux and Cheyenne to a stunning victory over Lieutenant Colonel George Custer (1839-76) and his men. The Indians were resisting the U.S. government’s efforts to force them back to their reservations. After Custer and over 200 of his soldiers were killed in the conflict, later dubbed “Custer’s Last Stand,” the American public wanted revenge. As a result, the U.S. Army launched a winter campaign in 1876-77, led by General Nelson Miles (1839-1925), against the remaining hostile Indians on the Northern Plains.

Combining military force with diplomatic overtures, Nelson convinced many Indians to surrender and return to their reservations. Much to Nelson’s frustration, though, Sitting Bull refused to give in and fled across the border to Canada, where he and his people remained for four years before finally returning to the U.S. to surrender in 1881. Sitting Bull died in 1890. Meanwhile, Crazy Horse and his band also refused to surrender, even though they were suffering from illness and starvation.

On January 8, 1877, General Miles found Crazy Horse’s camp along Montana’s Tongue River. U.S. soldiers opened fire with their big wagon-mounted guns, driving the Indians from their warm tents out into a raging blizzard. Crazy Horse and his warriors managed to regroup on a ridge and return fire, but most of their ammunition was gone, and they were reduced to fighting with bows and arrows. They managed to hold off the soldiers long enough for the women and children to escape under cover of the blinding blizzard before they turned to follow them.

Though he had escaped decisive defeat, Crazy Horse realized that Miles and his well-equipped cavalry troops would eventually hunt down and destroy his cold, hungry followers. On May 6, 1877, Crazy Horse led approximately 1,100 Indians to the Red Cloud reservation near Nebraska’s Fort Robinson and surrendered. Five months later, a guard fatally stabbed him after he allegedly resisted imprisonment by Indian policemen.

In 1948, American sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski began work on the Crazy Horse Memorial, a massive monument carved into a mountain in South Dakota. Still a work in progress, the monument will stand 641 feet high and 563 feet long when completed.

———-

1918 — Mississippi became the first state to ratify the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, which established Prohibition.

1918 — U.S. President Woodrow Wilson discussed the aims of the United States in World War I and outlined his “14 Points” for achieving a lasting peace in Europe before a joint session of Congress. The peace proposal called for unselfish peace terms from the victorious Allies, the restoration of territories conquered during the war, the right to national self-determination, and the establishment of a postwar world body to resolve future conflict. The speech was translated and distributed to the soldiers and citizens of Germany and Austria-Hungary and contributed significantly to their agreeing to an armistice in November 1918.

After the war ended, Wilson traveled to France, where he headed the American delegation to the conference at Versailles. Functioning as the moral leader of the Allies, Wilson struggled to orchestrate a just peace, though the other victorious Allies opposed most of his 14 Points. The final treaty called for stiff reparations payments from the former Central Powers and other demanding peace terms that would contribute to the outbreak of World War II two decades later. However, Wilson’s ideas on national self-determination and a postwar world body were embodied in the treaty. In 1920, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

———-

1919 — Ballerina Nana Gollner was born in El Paso. She began ballet training at age four as treatment for infantile paralysis. She continued dance lessons after moving to Los Angeles, making her first professional appearance there at age fourteen. In her teens, Gollner also performed with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. During the 1940s she appeared alternately with the American Ballet Theatre, the Ballet Russe, and the London-based International Ballet. With the latter, she became the first twentieth-century North American to gain prima ballerina roles in a European company. While best known for performances in classical ballets such as Giselle and Swan Lake, she also performed memorable parts in works by modern choreographers Anton Dolin, George Balanchine, and Antony Tudor. Gollner married Danish dancer Paul Eilif Petersen in 1942. Frequent dance partners, they used the professional names of Nana Gollner and Paul Petroff. In 1948 Gollner and Petroff formed their own company and toured Europe and South America. In 1950 Gollner returned to New York to perform with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet, later known as American Ballet Theatre. The Gollner-Petroff company resumed touring in 1951, and in 1952 Gollner and her family moved to Belgium. She died in Antwerp in 1980.

1935 — Rock-and-roll legend Elvis Presley was born in Tupelo, Mississippi.

———-

1941 — One of Hollywood’s most famous clashes of the titans—an upstart “boy genius” filmmaker versus a furious 76-year-old newspaper tycoon—heated up when William Randolph Hearst forbade any of his newspapers to run advertisements for Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane.

Though Welles was only 24 years old when he began working in Hollywood, he had already made a name for himself on the New York theater scene and particularly with his controversial radio adaptation of the H.G. Wells novel The War of the Worlds in 1938. After scoring a lucrative contract with the struggling RKO studio, he was searching for an appropriately incendiary topic for his first film when his friend, the writer Herman Mankiewicz, suggested basing it on the life of William Randolph Hearst. Hearst was a notoriously innovative, often tyrannical businessman who had built his own nationwide newspaper empire and owned eight homes, the most notable of which was San Simeon, his sprawling castle on a hill on the Central California coast.

After catching a preview screening of the unfinished Citizen Kane on January 3, 1941, the influential gossip columnist Hedda Hopper wasted no time in passing along the news to Hearst and his associates. Her rival and Hearst’s chief movie columnist, Louella Parsons, was incensed about the film and its portrait of Charles Foster Kane, the Hearst-like character embodied in typically grandiose style by Welles himself. Even more loathsome to Hearst and his allies was the portrayal of Kane’s second wife, a young alcoholic singer with strong parallels to Hearst’s mistress, the showgirl-turned-actress Marion Davies. Hearst was said to have reacted to this aspect of the film more strongly than any other, and Welles himself later called the Davies-based character a “dirty trick” that he expected would provoke the mogul’s anger.

Only a few days after the screening, Hearst sent the word out to all his publications not to run advertisements for the film. Far from stopping there, he also threatened to make war against the Hollywood studio system in general, publicly condemning the number of “immigrants” and “refugees” working in the film industry instead of Americans, a none-too-subtle reference to the many Jewish members of the Hollywood establishment. Hearst’s newspapers also went after Welles, accusing him of Communist sympathies and questioning his patriotism.

Hollywood’s heavyweights, who were already resentful of Welles for his youth and his open contempt for Hollywood, soon rallied around Hearst. Louis B. Mayer of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer even offered to pay RKO $842,000 in cash if the studio’s president, George Schaefer, would destroy the negative and all prints of Citizen Kane. Schaefer refused and in retaliation threatened to sue the Fox, Paramount and Loews theater chains for conspiracy after they refused to distribute the film. After Time and other publications protested, the theater chains relented slightly and permitted a few showings; in the end, the film barely broke even.

Nominated for nine Oscars, Citizen Kane won only one (a shared Best Screenplay award for Mankiewicz and Welles), and Welles and the film were actually booed at the 1942 Academy Awards ceremony. Schaefer was later pushed out at RKO, along with Welles, and the film was returned to the RKO archives. It would be 25 more years before Citizen Kane received its rightful share of attention, but it has since been heralded as one of the best movies of all time.

———-

1946 — President Harry S. Truman vowed to stand by the Yalta accord on self-determination for the Balkans.

1954 — President Dwight D. Eisenhower proposed stripping convicted Communists of their U.S. citizenship.

1958 — Bobby Fischer won the United States Chess Championship at age 14.

———-

1959 — A triumphant Fidel Castro entered Havana, having deposed the American-backed regime of General Fulgencio Batista. Castro’s arrival in the Cuban capital marked a definitive victory for his 26th of July Movement and the beginning of Castro’s decades-long rule over the island nation.

The revolution had gone through several stages, beginning with a failed assault on a barracks and Castro’s subsequent imprisonment in 1953. After his release and exile in Mexico, he and 81 other revolutionaries arrived back in Cuba on a small yacht, the Granma, in 1956. Over the course of the next two years, Castro’s forces and other rebels fought what was primarily a guerrilla campaign, frustrating the significantly larger forces of Batista. After a failed offensive by Batista’s army, Castro’s guerrillas descended from their hideouts in the southern mountains and began to make their way northwest, toward Havana. Outnumbered but supported by most of the civilians they encountered along the way, Generals Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos captured the city of Santa Clara on December 31, 1958, prompting Batista to flee the country. When he heard the news, Castro began what was essentially a victory parade, arriving in Havana a week later.

Castro became Prime Minister of Cuba the following month and played a leading role in the construction of a new state. Contrary to commonly held beliefs, he did not immediately institute a communist regime. Rather, he quickly set out on a goodwill tour of the United States, where President Dwight D. Eisenhower refused to meet with him, and traveled the Americas gathering support for his proposal that the U.S. do for its own hemisphere what it had done for Europe with the Marshall Plan.

Despite these overtures, Castro’s government would inevitably become aligned with the other side of the Cold War divide. Castro’s reforms included the redistribution of wealth and land and other socialist priorities that were unfriendly to foreign businesses, leading to a feud with the United States and a close alliance with the Soviet Union. This rivalry—which nearly led to a nuclear war between the superpowers just three years later—has shaped the recent history of the region. Castro would rule until the early 2000s when he was replaced by his brother. During that time, an American embargo of Cuba stymied Castro’s dreams of a socialist republic, and hundreds of thousands fled his increasingly despotic regime. The Cuba that he left behind was a far cry from the one he hoped to build as he entered Havana, but Castro remains one of the most influential political figures of the 20th century. He died in 2016.

———-

1962 — Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, was exhibited at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.—its first-ever American showing. Over 2,000 dignitaries, including President John F. Kennedy, viewed the famous painting that evening. The next day the exhibit opened to the public, and during the next three weeks, an estimated 500,000 people viewed it. The painting then traveled to New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it was seen by another million people. Leonardo da Vinci, one of the great Italian Renaissance painters, completed the Mona Lisa, a portrait of the wife of wealthy Florentine citizen Francesco del Gioconda, in 1504. The painting, also known as La Gioconda, depicts the figure of a woman with an enigmatic facial expression that is both aloof and alluring, seated before a visionary landscape. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and Andre Malraux, the French minister of culture, arranged the loan of the painting from the Louvre Museum in Paris to the United States.

1964 — President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a “War on Poverty” in the United States.

1967 — About 16,000 U.S. soldiers from the 1st and 25th Infantry Divisions, 173rd Airborne Brigade, and 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment joined 14,000 South Vietnamese troops to mount Operation Cedar Falls in Vietnam. This offensive, the largest of the war to date, was designed to disrupt insurgent operations near Saigon and had as its primary targets the Thanh Dien Forest Preserve and the Iron Triangle, a 60-square-mile area of jungle believed to contain communist base camps and supply dumps. During the operations, U.S. infantrymen discovered and destroyed a massive tunnel complex in the Iron Triangle, apparently a headquarters for guerrilla raids and terrorist attacks on Saigon. The operation ended with 711 of the enemy reported killed and 488 captured. Allied losses were 83 killed and 345 wounded. The operation lasted for 18 days.

1973 — National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and Hanoi’s Le Duc Tho resumed peace negotiations in Paris. After the South Vietnamese had blunted the massive North Vietnamese invasion launched in the spring of 1972, Kissinger and the North Vietnamese had finally made some progress on reaching a negotiated end to the war. However, a recalcitrant South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu had inserted several demands into the negotiations that caused the North Vietnamese negotiators to walk out of the talks on December 13. President Richard Nixon issued an ultimatum to Hanoi to send its representatives back to the conference table within 72 hours “or else.” The North Vietnamese rejected Nixon’s demand and the president ordered Operation Linebacker II, a full-scale air campaign against the Hanoi area. On December 28, after 11 days of round-the-clock bombing (with the exception of a 36-hour break for Christmas), North Vietnamese officials agreed to return to the peace negotiations in Paris. When the negotiators returned on January 8, the peace talks moved along quickly. On January 23, 1973, the United States, North Vietnam, the Republic of Vietnam, and the Viet Cong signed a cease-fire agreement that took effect five days later.

1973 — The trial of seven men accused of illegal entry into Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate began.

1975 — Judge John J. Sirica ordered the early release from prison of Watergate figures John W. Dean III, Herbert W. Kalmbach, and Jeb Stuart Magruder.

1975 — Ella Grasso became Governor of Connecticut, becoming the first woman to serve as a Governor in the United States other than by succeeding her husband.

1979 — The United States advised the Shan to leave Iran.

1982 — AT&T settled the Justice Department’s antitrust lawsuit against it by agreeing to divest itself of the 22 Bell System companies.

1987 — The Dow Jones industrial average closed above 2,000 for the first time, ending the day at 2,002.25.

1998 — Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, was sentenced in New York to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

2000 — In an American Football Conference (AFC) wild card match-up at Adelphia Coliseum in Nashville, Tennessee, the Tennessee Titans staged a last-second come-from-behind victory to beat the Buffalo Bills 22-16 on a kickoff return play later dubbed the “Music City Miracle.”

2002 — President George W. Bush signed into law the “No Child Left Behind Act,” intended to improve America’s educational system.

2004 — A U.S. Black Hawk medivac helicopter crashed near Fallujah, Iraq, killing all nine soldiers aboard.

2005 — The nuclear sub USS San Francisco collided at full speed with an undersea mountain south of Guam. One man was killed, but the sub surfaced and was repaired.

2008 — Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton powered to victory in New Hampshire’s 2008 Democratic primary in a startling upset, defeating Sen. Barack Obama and resurrecting her bid for the White House.

2008 — Sen. John McCain defeated his Republican rivals to move back into contention for the GOP nomination.

2008 — U.S. Army Lt. Col. Steven L. Jordan, the only officer charged in the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal, was cleared of criminal wrongdoing.

2009 — President-elect Barack Obama urged lawmakers to work with him “day and night, on weekends if necessary” to approve the largest taxpayer-funded stimulus ever.

2009 — Obama named Virginia Gov. Tim Kaine the next Democratic National Committee chairman.

2009— The U.N. Security Council called for an immediate cease-fire in Gaza by a 14-0 vote, with the United States abstaining.

2009 — No. 1 Florida beat No. 2 Oklahoma 24-14 for the BCS national title.

2010 — Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, accused of trying to blow up a U.S. airliner on Christmas, appeared in federal court in Detroit; the judge entered a not-guilty plea on his behalf. Abdulmutallab eventually pleaded guilty and is serving a life prison term.

2011 — An attempted assassination of Arizona congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords and subsequent shooting in Casas Adobes, Arizona at a Safeway grocery store killed six people and wounded 13, including Giffords. Gunman Jared Lee Loughner was sentenced in November 2012 to seven consecutive life sentences, plus 140 years.

2014 — Emails and text messages obtained by The Associated Press and other news organizations suggested that one of New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie’s top aides engineered traffic jams in Fort Lee in September 2013 to punish its mayor for not endorsing Christie for re-election; Christie responded by saying he’d been misled by the aide, and he denied involvement in the apparent act of political payback.

2014 — Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, and Frank Thomas were elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame.

2015 — Three dissidents were abruptly released in what a leading human rights advocate said was part of Cuba’s deal with Washington to release 53 members of the island’s political opposition.

2015 — Sen. Barbara Boxer, D-Calif., a tenacious liberal whose election to the Senate in 1992 heralded a new era for women at the upper reaches of political power, announced she would not seek re-election.

2015 — During a daylong meeting at the Denver airport, U.S. Olympic Committee board members chose Boston over Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, to bid for the 2024 Summer Olympics.

———-

2016 — Mexican authorities apprehend the drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. It was the third time that the law caught up to El Chapo, a figure whose crimes, influence, and mystique rival those of Pablo Escobar.

Guzmán became involved in the drug trade as a child, dealing in cocaine, heroin, marijuana, and amphetamines. He became the leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, the wealthiest and most powerful cartel in Mexico. After his arrest in Guatemala in 1993, Guzmán was extradited to Mexico and sentenced to over 20 years in prison. While incarcerated, he continued to run the cartel and lived comfortably, having bribed much of the staff. In 2001, when a Mexican Supreme Court ruling increased the likelihood that he would be extradited to the United States, Guzmán escaped by hiding in a laundry cart – over 70 people, including the director of the prison, have been implicated in his escape.

Guzmán remained at large for over a decade, leading the cartel through a vicious series of conflicts with the government and rival cartels. One of the central conflicts revolved around Guzmán’s bloody and ultimately successful bid for control over the Ciudad Juárez routes that transport drugs into the United States. Guzmán became infamous for his cartel’s extreme violence and its extensive network of tunnels and distribution cells on both sides of the border. It was widely known that the Sinaloa Cartel had a number of informants and agents within the Mexican government, and many in Mexico believed that the government’s war on drugs was actually being waged to eliminate Sinaloa’s rivals.

Burgoyne published his first play, “The Maid of the Oaks,” in 1774. It was well received and soon opened at the Drury Lane Theater for a run of several nights to both good and bad reviews, but Burgoyne had established his name as a playwright. When Burgoyne was sent to Boston in May 1775, he used his influence to have Faneuil Hall converted into a theater. One of the ways bored British soldiers trapped in Boston spent their time was in producing plays twice a week on the upper level of Faneuil Hall, to the complete consternation of Boston’s Puritan population, which had outlawed theater performances since 1750, believing them to be instigators of “immorality, impiety, and contempt of religion.

Finally, nearly six months later, an operation involving every law enforcement agency in Mexico resulted in a raid of a house in Los Mochis, Sinaloa. Guzmán escaped the house— again through a tunnel—and stole a car, but was captured near the town of Juan José Ríos. It was later revealed that the Mexican government had consulted with the Colombian and American law enforcement agents who tracked down and killed Escobar during the manhunt. In a tacit acknowledgment of its prior missteps, the Mexican government expedited Guzmán to the United States in 2017. He was convicted on a slew of charges and sentenced to life in prison.

Guzmán is currently held at ADX Florence, said to be the most secure prison in the federal penitentiary system, in Colorado. The Mexican Drug War continues, with rivalries within the Sinaloa Cartel and the rise of new cartels contributing to an atmosphere of violence and terror that has persisted even in the absence of the country’s most storied drug lord.

———-

2018 — The Trump administration said it was ending special protections for immigrants from El Salvador, an action that could force nearly 200,000 to leave the U.S. by September 2019 or face deportation.

2019 — Alabama beat Georgia in overtime, 26-23, to claim the College Football Playoff national championship after freshman quarterback Tua Tagovailoa came off the bench to spark a comeback.

2019 — A judge in Las Vegas dismissed criminal charges against Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy and his sons, who were accused of leading an armed uprising against federal authorities.

2019 — In a somber televised address, President Donald Trump urged congressional Democrats to fund his border wall and end the stalemate that had shut down much of the government for 18 days.

2019 — Mayor Bill de Blasio said New York City would spend up to $100 million per year to expand health care coverage to people without health insurance, including immigrants in the country illegally.

2020 — Iran struck back at the United States for killing Iran’s top military commander, firing missiles at two Iraqi military bases housing American troops; more than 100 U.S. service members were diagnosed with traumatic brain injuries after the attack. As Iran braced for a counterattack, the country’s Revolutionary Guard shot down a Ukrainian jetliner after apparently mistaking it for a missile; all 176 people on board were killed, including 82 Iranians and more than 50 Canadians.