Frederick Fleet, 24, the lookout who first spotted the iceberg. He went on to serve in both World Wars. In 1965, he experienced depression and later hanged himself.

The history of Titanic, of the White Star Line, is one of the most tragically short stories ever.

The world had waited expectantly for its launching and again for its sailing; had read accounts of its tremendous size and its unexampled completeness and luxury.

Had felt it a matter of the greatest satisfaction that such comfortable, and above all such a safe boat had been designed and built – the “unsinkable lifeboat”; – and then in a moment to hear that it had gone to the bottom with fifteen hundred passengers!

The improbability of such a thing ever happening was what staggered the world.

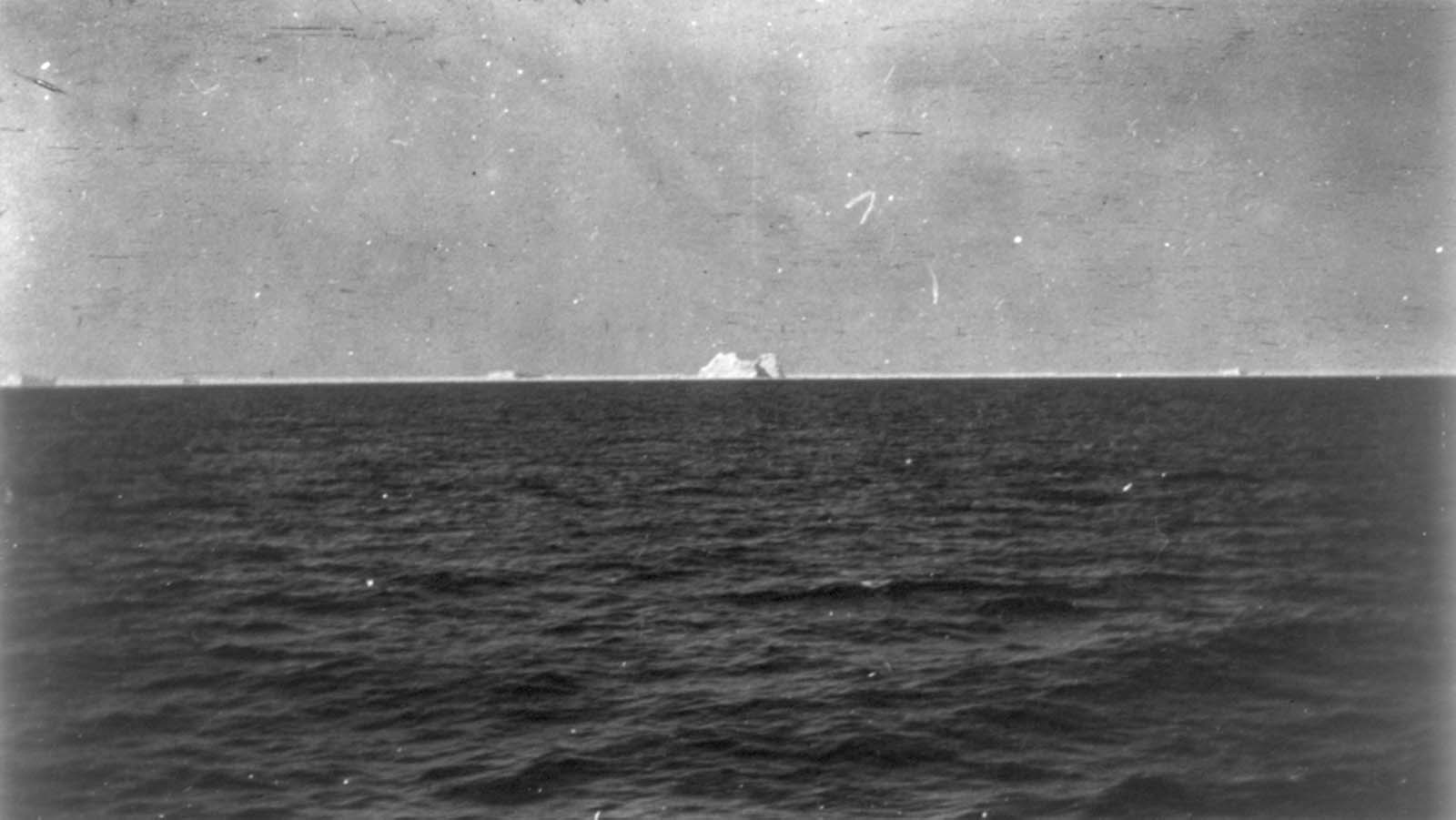

The iceberg that sank the Titanic.

If Titanic’s history had to be written in a single paragraph it would be somewhat as follows: “The R.M.S Titanic was built by Messrs. Harland & Wolf at their well-known shipbuilding works at Queen’s Island, Belfast, side by side with her sister ship the Olympic.

The Twin vessels marked such an increase in size that specially laid-out joiner and boiler shops were prepared to aid in their construction, and space usually taken up by three building slips was given up to them.

The keel of the Titanic was laid on March 31, 1909, and she was launched on May 31, 1911; she passed her trials before the Board of the Trade officials on March 31, 1912, at Belfast and arrived at Southampton on April 5, and sailed the following Wednesday, April 10, with 2,208 passengers and crew, on her maiden voyage to New York.

She called at Cherbourg the same day, Queenstown Thursday, and left for New York in the afternoon, expecting to arrive the following Wednesday morning.

But the voyage was never completed. She collided with an iceberg on Sunday at 11:45 PM and sank two hours and a half later; 815 of her passengers and 688 of her crew were drowned and 705 rescued by Carpathia.”

Titanic survivors approach the Carpathia.

In the immediate aftermath of the sinking, hundreds of passengers and crew were left dying in the icy sea, surrounded by debris from the ship.

Titanic’s disintegration during her descent to the seabed caused buoyant chunks of debris – timber beams, wooden doors, furniture, paneling, and chunks of cork from the bulkheads – to rocket to the surface.

Titanic’s survivors were rescued around 04:00 on 15 April by the RMS Carpathia, which had steamed through the night at high speed and at considerable risk, as the ship had to dodge numerous icebergs en route.

Carpathia’s lights were first spotted around 03:30, which greatly cheered the survivors, though it took several more hours for everyone to be brought aboard. In total, 705 survivors boarded on Carpathia.

Titanic survivors in a lifeboat.

When Carpathia arrived at Pier 54 in New York on the evening of 18 April after a difficult voyage through pack ice, fog, thunderstorms and rough seas, some 40,000 people were standing on the wharves, alerted to the disaster by a stream of radio messages from Carpathia and other ships.

It was only after Carpathia docked – three days after Titanic’s sinking – that the full scope of the disaster became public knowledge.

The prevailing public reaction to the disaster was one of shock and outrage, directed against several issues and people: why were there so few lifeboats?

Why had Ismay saved his own life when so many others died? Why did Titanic proceed into the ice field at full speed

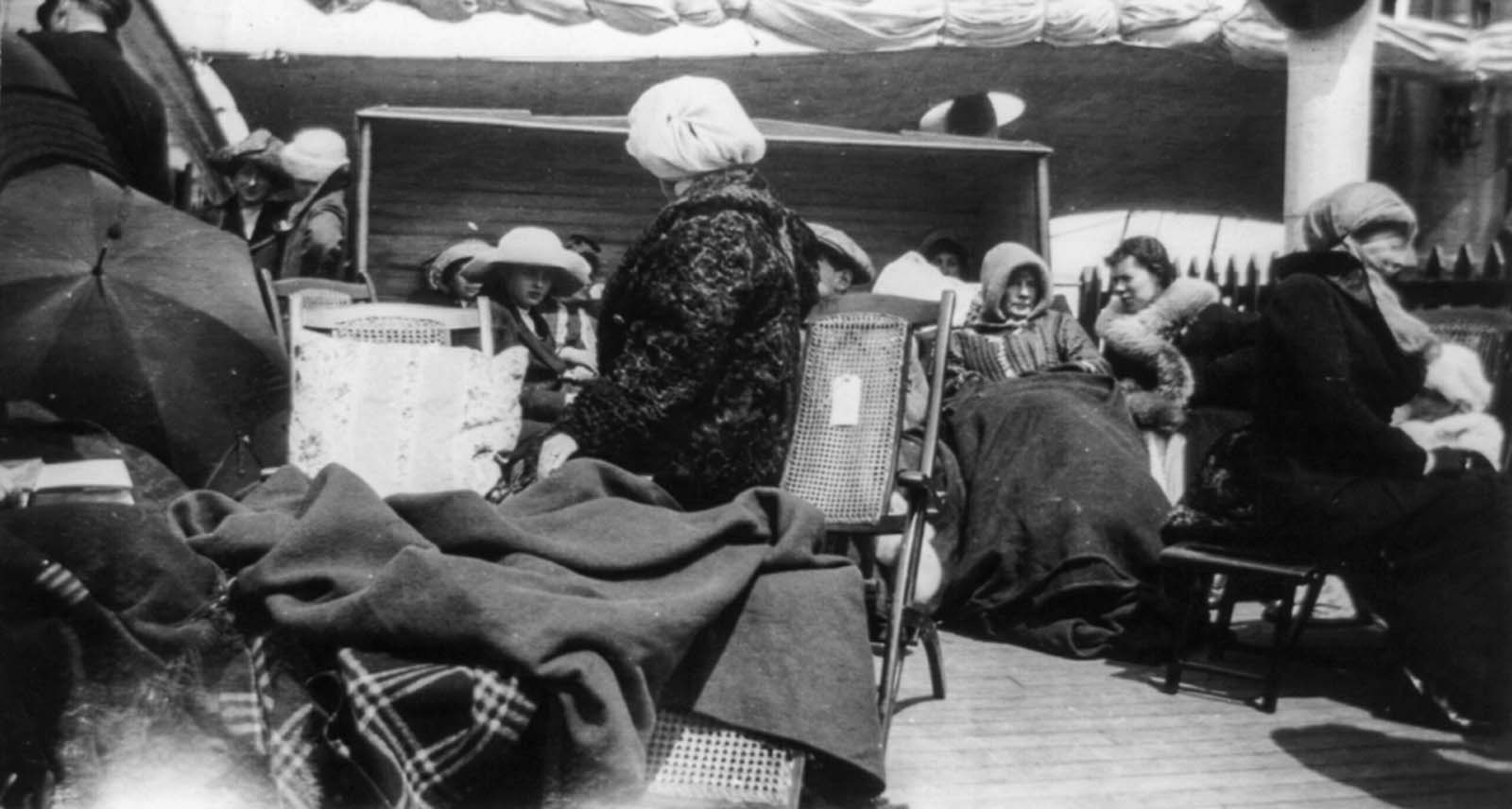

Survivors aboard the Carpathia.

The outrage was driven not least by the survivors themselves; even while they were aboard Carpathia on their way to New York, Beesley and other survivors determined to “awaken public opinion to safeguard ocean travel in the future” and wrote a public letter to The Times urging changes to maritime safety laws.

In places closely associated with Titanic, the sense of grief was deep. The heaviest losses were in Southampton, homeport to 699 crew members and also home to many of the passengers.

Crowds of weeping women – the wives, sisters, and mothers of the crew – gathered outside the White Star offices in Southampton for news of their loved ones.

Most of them were among the 549 Southampton residents who perished.

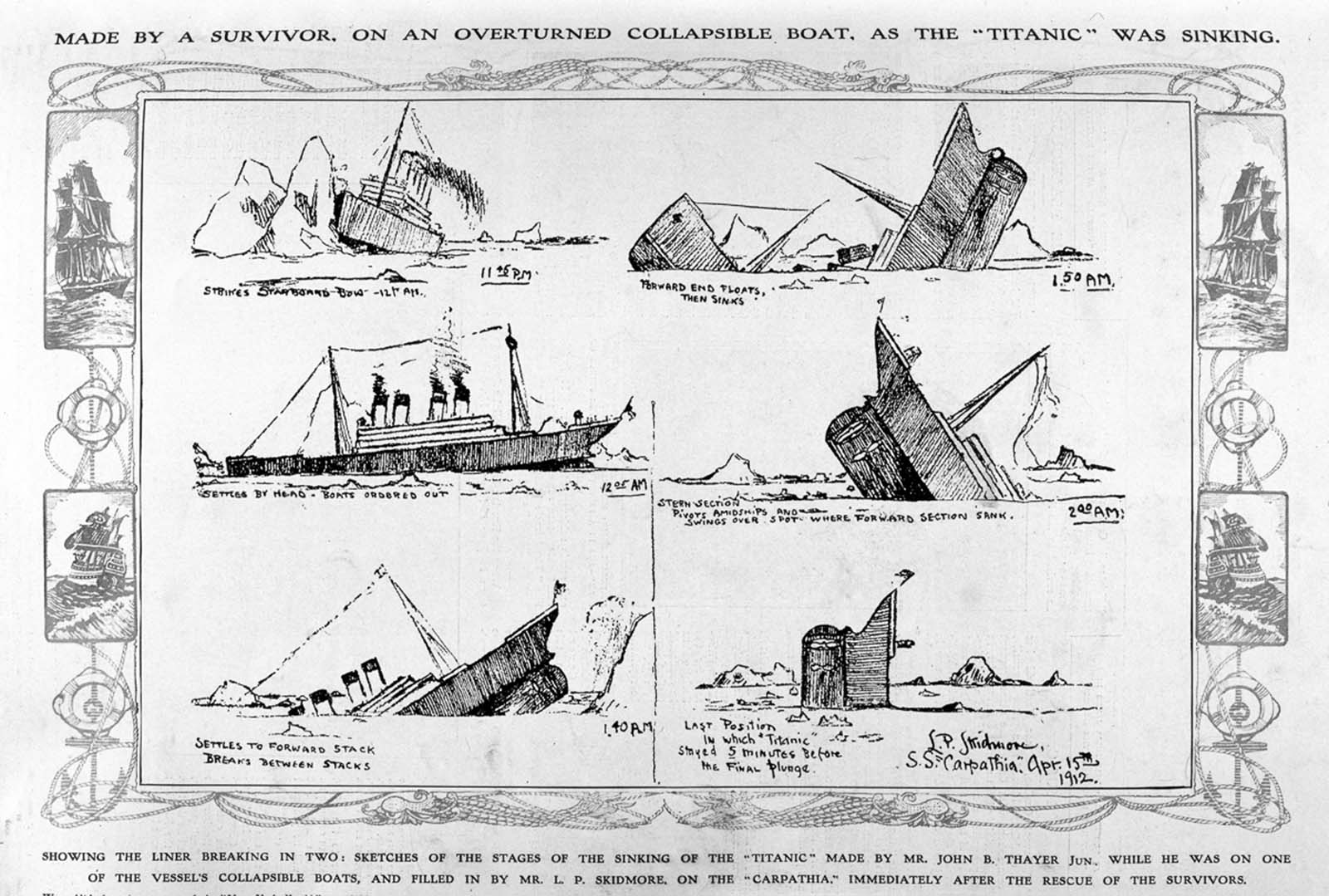

A sketch of the sinking drawn by John B. Thayer while he was on a capsized lifeboat, and filled in by P.L. Skidmore aboard the Carpathia.

In Belfast, churches were packed, and shipyard workers wept in the streets.

The ship had been a symbol of Belfast’s industrial achievements, and there was not only a sense of grief but also one of guilt, as those who had built Titanic came to feel they had been responsible in some way for her loss.

Survivors huddle for warmth on the deck of the Carparthia.

People wait for news outside the offices of the White Star Line in New York.

The Titanic’s lifeboats are returned to the berth of the White Star Line in New York.

Crowds stand in the rain awaiting the arrival of the Carpathia in New York.

Crowds await the arrival of the Carpathia in New York.

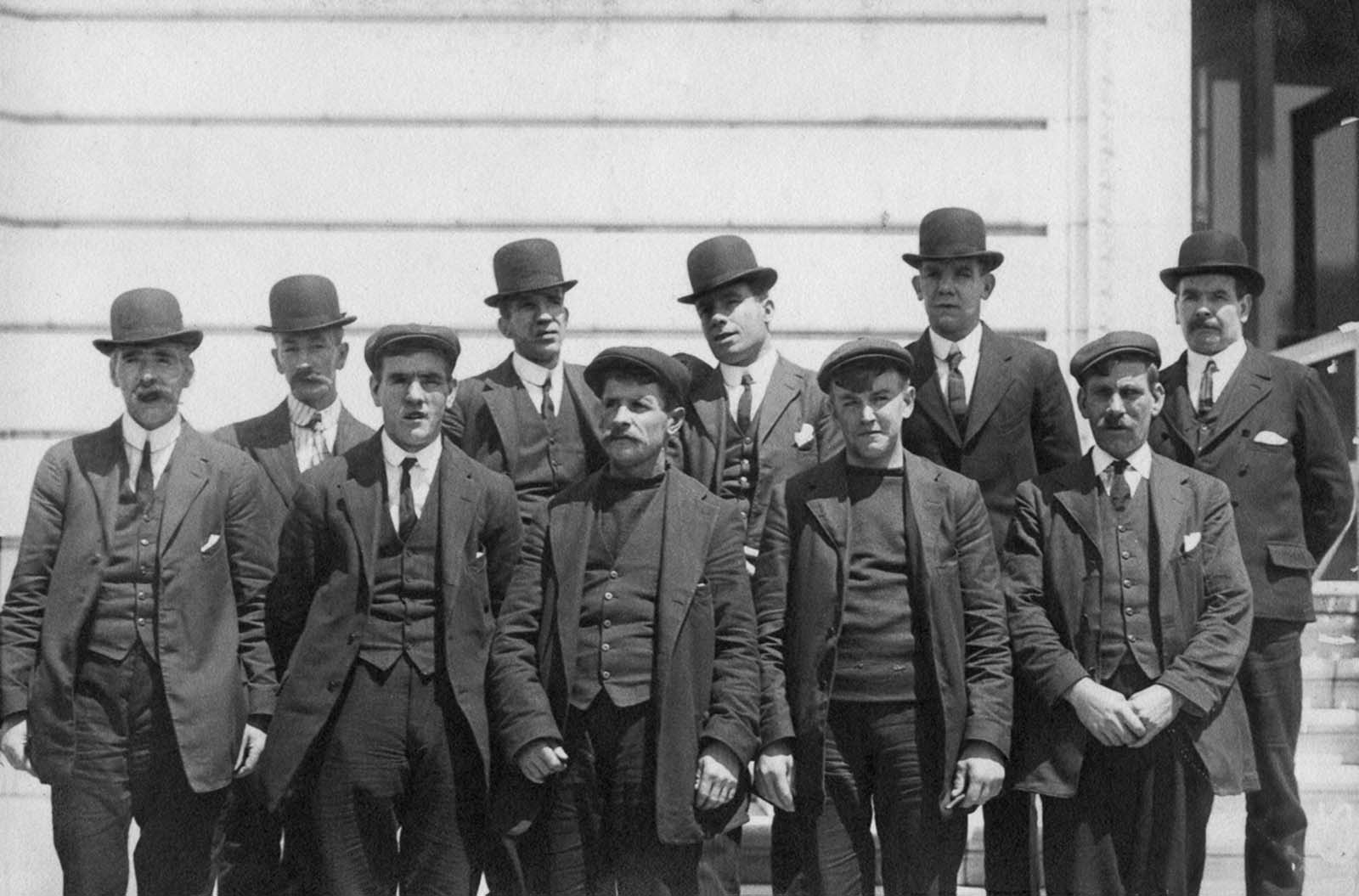

Surviving crew, from left to right, first row: Ernest Archer, Frederick Fleet, Walter Perkis, George Symons and Frederick Clench. Second row: Arthur Bright, George Hogg, John Moore, Frank Osman and Henry Etches.

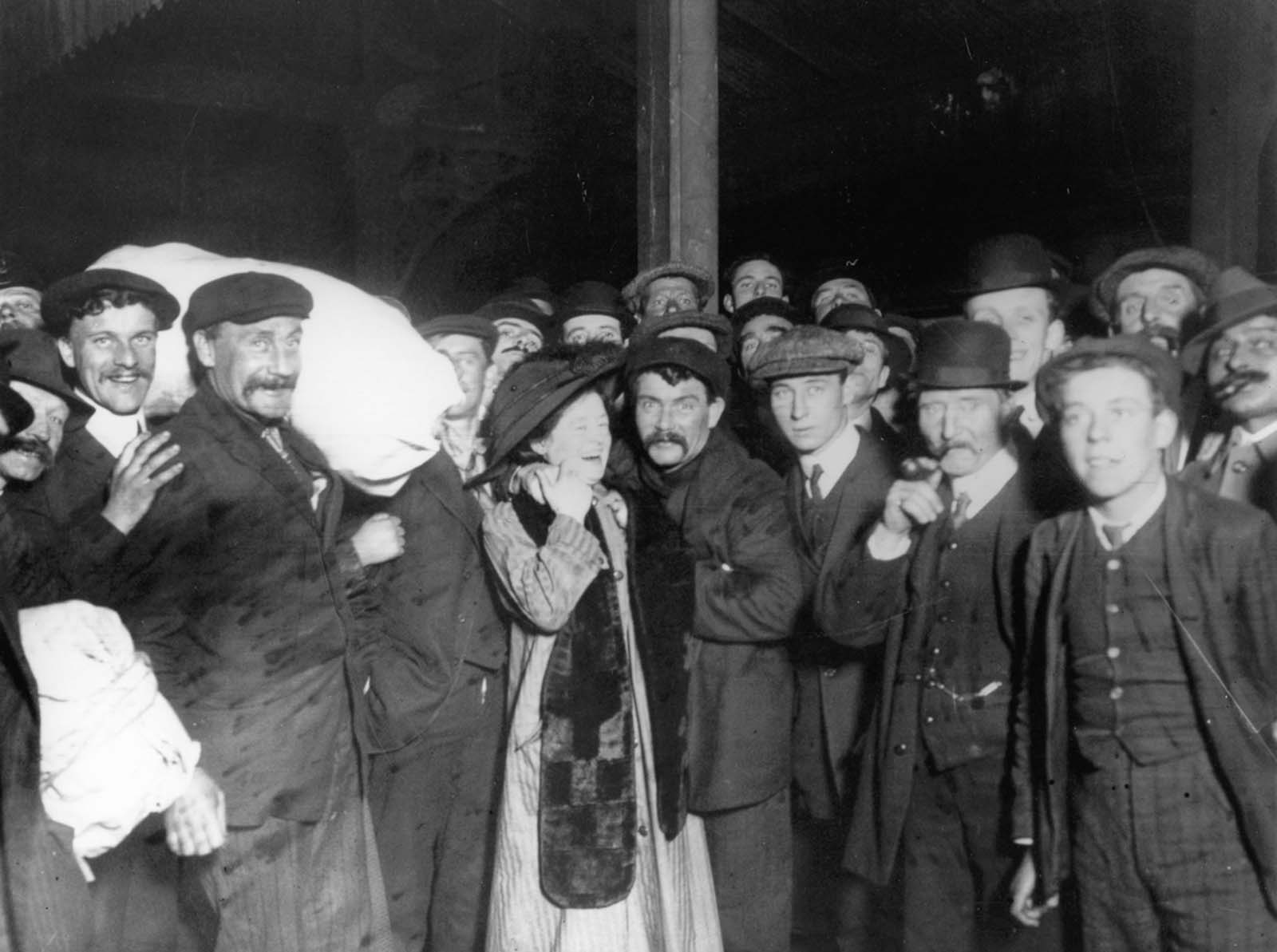

A crowd in Devonport gathers to hear a survivor tell his story.

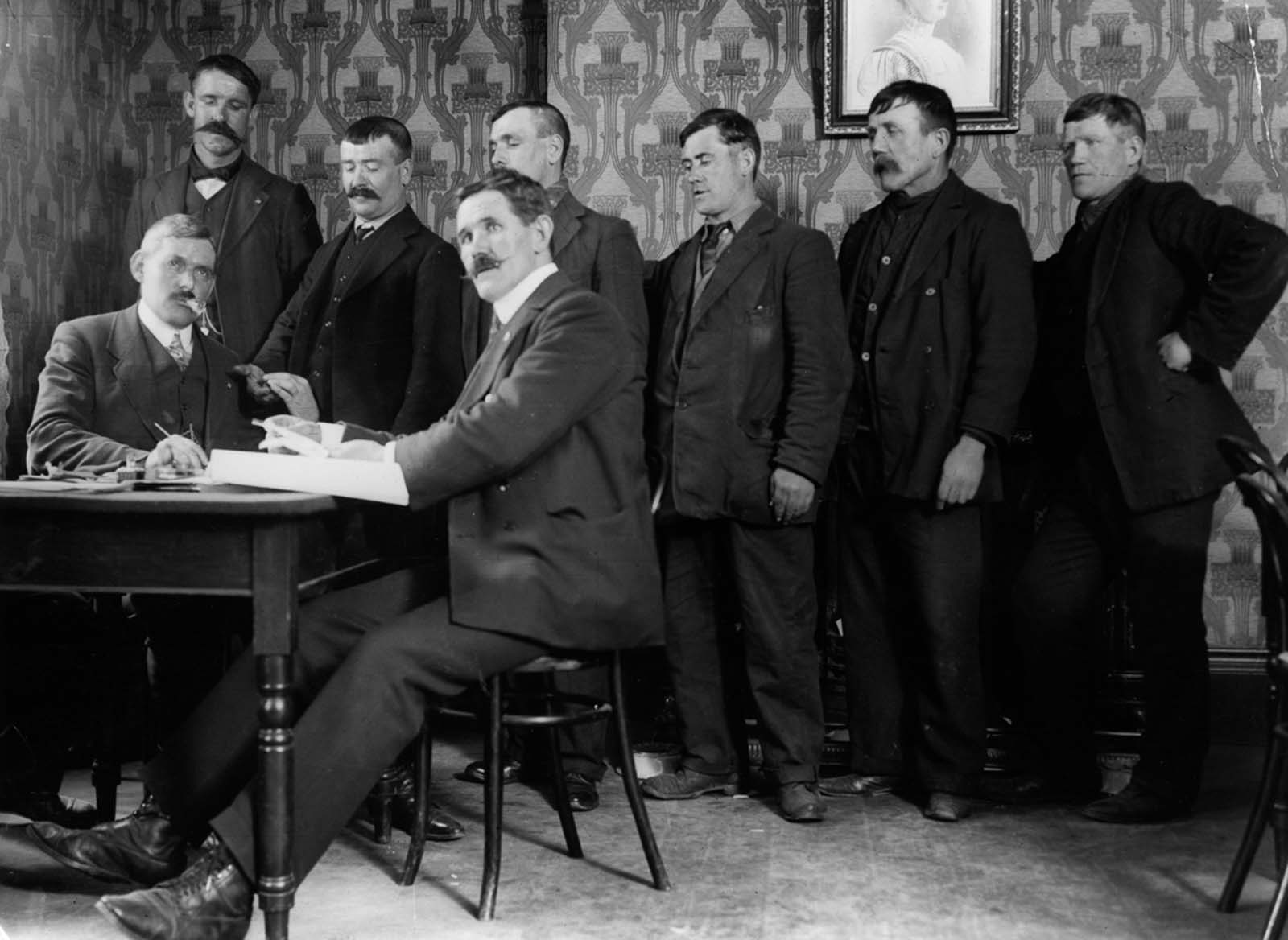

J. Hanson, seated right, district secretary of the National Sailors and Firemen’s Union, awards shipwreck pay to survivors.

Relatives wait on a railway platform as survivors of the Titanic arrive at Southampton.

Relatives wait for survivors at Southampton.

Relatives wait for the surviving crew to come ashore at Southampton.

Relatives wait for survivors at Southampton.

Relatives await survivors in Southampton.

Survivors are greeted by relatives upon their return to Southampton.

A surviving crew member kisses his wife upon arriving at Plymouth.

Surviving stewards line up outside a first-class waiting room before being called in for questioning by a board of inquiry.

A survivor gives a woman an autograph.

A survivor giving an autograph.

The four Pascoe brothers, crew who survived the sinking, return to Southampton.

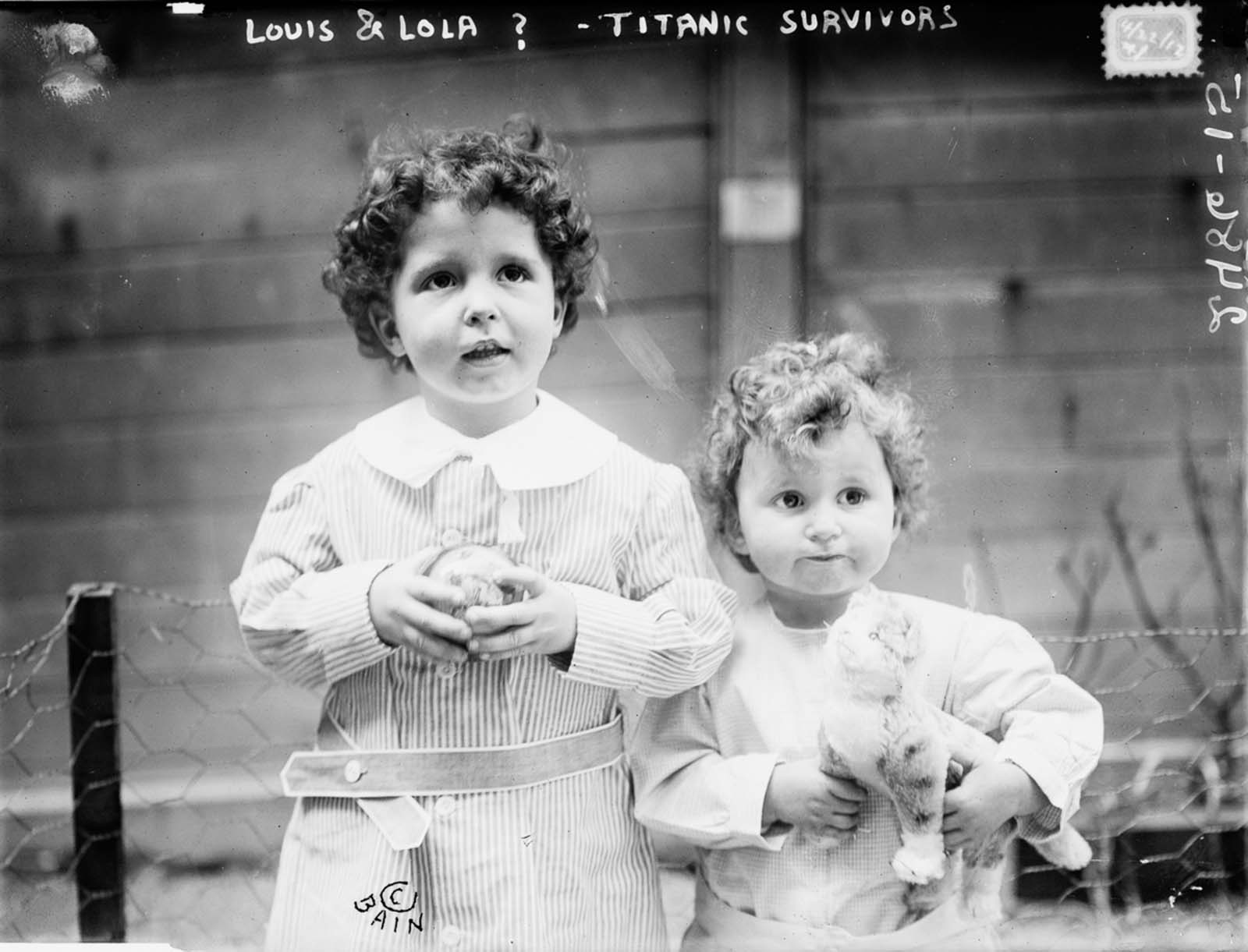

Unidentified survivors, later identified as Michel, 4 and Edmond Navratil, 2. To board the ship, their father assumed the name Louis Hoffman and used their nicknames, Lolo and Mamon.

Edmond and Michel Navratil are reunited with their mother.

Wireless operator Harold Thomas Coffin is questioned by a Senate committee at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York.

A nurse holds newborn Lucien P. Smith, Jr. His mother Eloise was pregnant with him while returning from her honeymoon aboard the Titanic. Lucien’s father died in the disaster. Eloise later married a fellow survivor, Robert P. Daniel.

(Photo credit: FPG / Hulton Archive / Getty Images / Library of Congress).